Back to series

William Tyndale: "Apostle of England"

Click here to open a Print - Friendly PDF

More than to any other person, we are indebted to William Tyndale for our English Bible.1 Apart from a few manuscript translations from the Latin, made at the time of John Wycliffe, the Bible was not available to English people in their own language. Tyndale was called by God, he believed, to provide a translation of the Bible so that even “a boy that driveth the plow” would be able to read and understand it.2 The keeping of that promise is the story of Tyndale’s life.

William Tyndale was born in 1494 in the remote west-country Forest of Dean on the border of Wales. He studied at Magdalen Hall, Oxford, earning his bachelor of arts degree in 1512 and his master’s three years later. Thomas More, who later became Tyndale’s bitter enemy, admitted that during his early life Tyndale was well known as “a man of right good living, studious and well learned in scripture, and in divers places in England was very well liked, and did great good with preaching.”3

After Oxford Tyndale spent a few years in Cambridge, furthering his biblical knowledge and absorbing the Lutheran ideas being discussed in the White Horse Inn and spreading throughout the country. In 1521 he became a tutor at Little Sodbury Manor, north of Bath. Probably already ordained as a priest, he was soon known as a preacher of evangelical convictions and penetrating power of expression.

England, unlike any major European country, was without a printed vernacular translation of the Bible. To translate the Bible into the vernacular was still illegal in England. For more than a hundred years, the Catholic authorities had seized fragments of the Wycliffe manuscript Bibles, forcing their owners to recant, even burning them at the stake. But Tyndale was not deterred. He went to London, hoping to receive encouragement. Soon, however, he came to believe that not only was there “no room” in London for him to translate the Bible, “but also that there was no place to do it in all England.”4

Tyndale left England in April 1524, never to return. He planned to publish Bible translations on the Continent for distribution in England. After traveling in Germany, probably spending some months in Wittenberg, he went to Cologne, one of the great trading ports of northeast Europe. When his work was disrupted by the magistrates of the city, Tyndale moved to Worms, where Luther had made his famous defense before the Diet a few years earlier. There, early in 1526, he successfully completed the translation and printing of the New Testament. Tyndale wrote in his prologue, “I have here translated (brothers and sisters most dear and tenderly beloved in Christ) the New Testament for your spiritual edifying, consolation and solace.”5 Tyndale’s New Testament was the first printed New Testament in English and his prologue, heavily dependent on Luther but also including his own ideas, was the first English Protestant tract. The pages of his New Testament were smuggled into England, where they found eager readers, despite the public burning of Bibles and books at St. Paul’s Cathedral.

Tyndale worked steadily, revising his New Testament translation, learning Hebrew so as to translate the Old Testament, and writing theological treatises to support the Reformation. He moved from city to city, seeking a place where he could safely work and have his translations sent across the sea and sold in England. It did not matter to Tyndale who did the work or got credit for it. He even offered to return to England and write no more if the king would allow the publication of an English translation of the Bible.

In 1531 Tyndale’s translation of the book of Jonah was published, and in 1534, the same year Martin Luther’s complete German Bible appeared, Tyndale’s New Testament was reprinted with corrections and revisions. He was now living in Antwerp, Belgium, a thriving city of trade where sympathetic English merchants protected and helped him.

In 1531 Tyndale’s translation of the book of Jonah was published, and in 1534, the same year Martin Luther’s complete German Bible appeared, Tyndale’s New Testament was reprinted with corrections and revisions. He was now living in Antwerp, Belgium, a thriving city of trade where sympathetic English merchants protected and helped him.

In his first extended treatise, The Parable of the Wicked Mammon, Tyndale treated the central Reformation doctrine, justification by faith. As Tyndale put it, “we are saved by faith in the promises of God, and not by a holy candle.”6 In this book Tyndale developed an extended illustration of the anointing of Jesus’ feet by Mary, summing up the story with the words: “Deeds are the fruits of love; and love is the fruit of faith.”7

C.S. Lewis writes that the theme or message of all Tyndale’s theological works was the same and notes that the repetition is intentional. “He is like a man sending messages in war, and sending the same message often because it is a chance if any one runner will get through.” Every line Tyndale wrote, adds Lewis, “was directly or indirectly devoted to the same purpose: to circulate the ‘gospel’ either by comment or translation.”8 Tyndale’s one message was that no one can be saved by good works, certainly not by the requirements of the Catholic Church, which was little more than a system of prudential bargaining with God.

We must see the law as it really is and despair, because we cannot begin to keep it. But after the frightening “thunder” of the law comes the sweet “rain” of the gospel. By the gift of faith we receive God’s forgiveness and are thereby enabled to love and serve him and to love people. Good works are not the cause of salvation, but they are its inseparable symptom. We are “loosed from the law” by fulfilling it. Once the tree has been made good (by no merit of its own), it will bear good fruit, almost as a by-product. It was the same message that was being preached in Wittenberg by Luther and would soon sound from Calvin’s pulpit in Geneva.

As Reformation writings circulated in England, opposition grew. Sir Thomas More called Tyndale’s Parable of the Wicked Mammon “a very treasury and well-spring of wickedness.”9 Despite efforts to prevent Luther’s books and Tyndale’s translations and treatises from reaching England, more and more people were obtaining and reading the contraband books.

Tyndale published The Obedience of a Christian Man in October 1528; it quickly crossed the sea to England. It was Tyndale’s most important book outside his translations of the Bible, full as it is of “mountain ranges of New Testament doctrine.” “If we had nothing from Tyndale but his Obedience,” David Daniell writes, “he would still be of high significance for the time.”10

Now a hunted man, Tyndale worked on the Pentateuch, having added a remarkable skill in Hebrew to his knowledge of Greek. He was delighted to find that Hebrew translated more easily into English than it did into Latin. Assisted by Miles Coverdale, Tyndale published a translation of the Pentateuch and finished the translation of Joshua through 2 Chronicles.

The erratic course of Henry VIII’s reign was creating confusion and tragedy in England. Young John Frith was burned on July 4, 1531, the first English Protestant martyr. As he died Frith commended his friend William Tyndale for his “faithful, clear, innocent heart.”11

Thomas More, England’s leading humanist, became increasingly involved in the anti-Lutheran and anti-Tyndale campaign. More believed that the Catholic Church was superior to Scripture because of its possession of the unwritten tradition. He stated that it was impossible for the Church to err. He urged the burning of all heretics. More opposed Bible translation into English, arguing that if the common people had a vernacular Bible they would get it wrong—especially the Epistle to the Romans, “containing such high difficulties as very few learned men can very well attain.”12

Tyndale answered More’s attack by describing “Christ’s elect church” as “the whole multitude of all repenting sinners that believe in Christ, and put their trust and confidence in the mercy of God, feeling in their hearts that God for Christ’s sake loveth them, and will be, or rather is, merciful unto them, and forgiveth them their sins.”13 Tyndale’s aim was to correct the faults of the Catholic Church, “to purge, not to destroy.” He did not “want to burn anyone alive, not even Master More,” writes Daniell.14

More replied to Tyndale in two large books, which Tyndale did not answer. Daniell sums up the exchange: “More gave us three quarters of a million words of scarcely readable prose attacking Tyndale. Tyndale outraged More by giving us the Bible in English.”15 C.S. Lewis comments that despite his faults as a writer, Tyndale was superior to More in his “joyous, lyric quality” and in his sentences that are “half way to poetry.”16

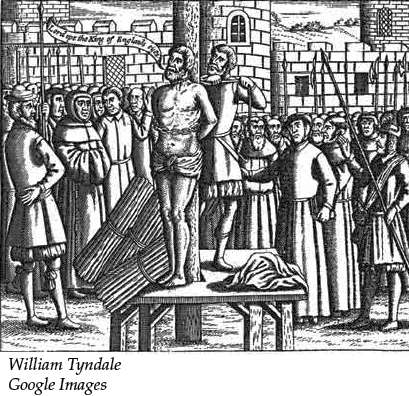

Betrayed by an English spy who was perhaps in the pay of Thomas More, Tyndale was arrested on May 21, 1535, and imprisoned near Brussels. Early in August 1536, after he had been in his cell for 450 days, he was formally condemned as a heretic, degraded from the priesthood, and handed over to the secular authorities for punishment—that is, burning at the stake.

While he was in prison, Tyndale wrote Faith Alone Justifies before God. The book has not survived, but there is no doubt what was in it. Once again Tyndale was trying to get his one message, the central message of the Bible, into the minds and hearts of the English people.

Only one writing from Tyndale during the year and a half in prison has survived, a letter, requesting:

. . . a warmer cap, for I suffer greatly from cold in the head, a warmer coat also, for this which I have is very thin; a piece of cloth too to patch my leggings. And I ask to be allowed to have a lamp in the evening; it is indeed wearisome sitting alone in the dark. But most of all I beg to have the Hebrew Bible, Hebrew grammar, and Hebrew dictionary, that I may pass the time in that study.

Tyndale’s words remind us of some of the last words of the apostle Paul, who wrote to Timothy urging him to “come before winter” and “bring the cloak that I left with Carpus at Troas, also the books, and above all the parchments” (2 Tim. 4:21, 13), words that Tyndale had lovingly translated into English with all the New Testament writings of Paul and much of the whole Bible.

Tyndale did not despair or fall into self-pity or bitterness, even reaching out to others in his suffering. John Foxe wrote that “such was the power of his doctrine, and the sincerity of his life, that during the time of his imprisonment, it is said, he converted his keeper, his keeper’s daughter, and others of his household.”17

Tyndale closed his last letter, writing that if a decision about his fate was made before winter, “I will be patient, abiding the will of God, to the glory of the grace of my Lord Jesus Christ.”18 While Tyndale was in prison in Belgium, Queen Anne Boleyn was executed on May 19, 1536, on the absurd charges of incest, adultery, and treason. Anne kept open in her chamber her own copy of Tyndale’s 1534 New Testament (now in the British Library).

Tyndale closed his last letter, writing that if a decision about his fate was made before winter, “I will be patient, abiding the will of God, to the glory of the grace of my Lord Jesus Christ.”18 While Tyndale was in prison in Belgium, Queen Anne Boleyn was executed on May 19, 1536, on the absurd charges of incest, adultery, and treason. Anne kept open in her chamber her own copy of Tyndale’s 1534 New Testament (now in the British Library).

While she lived, there was some hope that religious policy in England would become more favorable to the Protestant cause. But it did not come soon enough to save Tyndale. On October 6, 1536, a little over four months after Anne Boleyn’s death, William Tyndale was tied to the stake, strangled first by the hangman, and then his body was burned. Tyndale’s last words were a prayer for the success of his beloved Bible translation. “With a fervent zeal, and a loud voice,” he cried, “Lord! Open the King of England’s eyes.”19

His prayer was soon answered. Thomas Cromwell, the king’s principal adviser, and Thomas Cranmer, the archbishop of Canterbury, persuaded Henry VIII to approve an official English translation of the Bible. The king licensed the publication of fifteen hundred copies of a translation called Matthew’s Bible—largely a conflation of Tyndale’s work and that of Tyndale’s friends and assistants, Miles Coverdale and John Rogers (also known as Thomas Matthew). This became the first Bible in English to be legally sold in the country. Yet another translation, the Great Bible of 1539 (a slight revision of Matthew’s Bible), was ordered by the king to be placed in every parish church in England. Now everyone could come and read the Bible, even “the boy that driveth the plow.”

Tyndale was both an able scholar (fluent in seven languages in addition to English) and “a conscious craftsman” with an “extraordinary gift for uniting the skill of making sense of an original with the music of spoken English at its best.”20 He succeeded in making the Greek New Testament and the Hebrew Old Testament speak in remarkably clear, beautiful and vigorous English. His work made the English a Bible-reading people and influenced future translations down to the present. Because William Tyndale gave the English people the Bible in their own language, he is rightly honored as the “apostle of England.”

Not a few of Tyndale’s translations have become a part of the English language, including the following:

• “A city that is set on a hill cannot be hid.”

• “No man can serve two masters.”

• “Ask and it shall be given you. Seek and ye shall find. Knock and it shall be opened unto you.”

• “Give unto one of these little ones to drink, a cup of cold water only.”

• “The spirit is willing.”

• “Fight the good fight.”

• “In him we live and move and have our being.”

• “With God all things are possible.”

• “Be not weary in well doing.”

• “Behold, I stand at the door and knock.”

| Notes: 1. The Latin inscription at the bottom of the portrait of William Tyndale that hangs in the dining hall of Hertford College, Oxford, reads in part, “This picture represents, as far as art could, William Tyndale . . . who, after establishing here the happy beginnings of a purer theology, at Antwerp devoted his energies to translating into the vernacular the New Testament and the Pentateuch, a labour so greatly tending to the salvation of his fellow-countrymen that he was rightly called the Apostle of England.” Cited in David Daniell, William Tyndale: A Biography (New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 1994), after p. 214. Magisterial in every sense of the word, Daniell’s William Tyndale is the best book to consult for Tyndale’s life and work. Daniell skillfully uses many sources, including The Acts and Monuments of John Foxe, quoting, summarizing, and clarifying Foxe’s material. 2. Daniell, William Tyndale, 1. 3. Ibid., 39. 4. Biographical Dictionary of Evangelicals (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity, 2003), 678. 5. Daniell, William Tyndale, 108. 6. Ibid., 156. 7. Ibid., 165. 8. C.S. Lewis, English Literature in the Sixteenth Century (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1954), 182. 9. Daniell, William Tyndale, 170. 10. Ibid., 232, 223. 11. Ibid., 219. 12. Ibid., 269. 13. Ibid., 270. 14. Ibid., 271. 15. Ibid., 280. 16. Lewis, English Literature, 192. 17. Daniell, William Tyndale, 381. 18. Ibid., 379. 19. Ibid., 383. It is estimated that by the time of Tyndale’s martyrdom in 1536 as many as sixteen thousand copies of his translation had reached England. Few copies still exist, only two of his 1526 translation of the New Testament. Copies not burned were simply read to pieces. 20. Ibid., 48, 92. |

|||

David B. Calhoun

ProfessorDavid B. Calhoun, (1937-2021) was Professor Emeritus of Church History at Covenant Theological Seminary in St. Louis, Missouri. A minister of the Presbyterian Church in America, he has taught at Covenant College, Columbia Bible College (now Columbia International University), and Jamaica Bible College (where he was also principal). Calhoun has served with Ministries in Action in the West Indies and in Europe and as dean of the Iona Centres for Theological Study. He was a board member (and for some years president) of Presbyterian Mission International, a mission board that assists nationals who are Covenant Seminary graduates to return to their homelands for ministry.

COPYRIGHT: This publication is published by C.S. Lewis Institute; 8001 Braddock Road, Suite 301; Springfield, VA 22151. Portions of the publication may be reproduced for noncommercial, local church or ministry use without prior permission. Electronic copies of the PDF files may be duplicated and transmitted via e-mail for personal and church use. Articles may not be modified without prior written permission of the Institute. For questions, contact the Institute: 703.914.5602 or email us.

COPYRIGHT: This publication is published by C.S. Lewis Institute; 8001 Braddock Road, Suite 301; Springfield, VA 22151. Portions of the publication may be reproduced for noncommercial, local church or ministry use without prior permission. Electronic copies of the PDF files may be duplicated and transmitted via e-mail for personal and church use. Articles may not be modified without prior written permission of the Institute. For questions, contact the Institute: 703.914.5602 or email us.

-

Recent Podcasts

Questions That Matter – Pippa Cramer and The Hymns We Love

by Pippa Cramer, Randy Newman on February 21, 2025Many people grew up singing Christian hymns. Pippa...Read More

-

Conversational Apologetics

by Michael Ramsden, Aimee Riegert on February 21, 2025

-

Questions That Matter – Heather and Ashley Holleman and the Greatness of Conversation

by Randy Newman, Heather Holleman on February 14, 2025

-

Recent Publications

The Impact of Technology on the Christian Life

by Tony Reinke on February 14, 2025"It’s applied technique. So it’s an art. It’s...Read More

-

C.S. Lewis and the Crisis of the Modern Self

by Thiago M. Silva on February 1, 2025

-

Why Are Christians So Hypocritical?

by William L. Kynes on January 1, 2025

0

All Booked

0.00

All Booked

0.00

All Booked

23993

Heart and Mind Discipleship Live Online Small Group 8:00 PM ET

https://www.cslewisinstitute.org/?event=heart-and-mind-discipleship-live-online-small-group-800-pm-et&event_date=2025-02-25®=1

https://www.paypal.com/cgi-bin/webscr

2025-02-25

Next coming event

Days

Hours

Minutes

Seconds

Heart and Mind Discipleship Live Online Small Group 8:00 PM ET

On February 25, 2025 at 8:00 pmSpeakers

David B. Calhoun

Professor

Team Members

David B. Calhoun

ProfessorDavid B. Calhoun, (1937-2021) was Professor Emeritus of Church History at Covenant Theological Seminary in St. Louis, Missouri. A minister of the Presbyterian Church in America, he has taught at Covenant College, Columbia Bible College (now Columbia International University), and Jamaica Bible College (where he was also principal). Calhoun has served with Ministries in Action in the West Indies and in Europe and as dean of the Iona Centres for Theological Study. He was a board member (and for some years president) of Presbyterian Mission International, a mission board that assists nationals who are Covenant Seminary graduates to return to their homelands for ministry.