Back to series

Recommended Reading:

Download or Listen to Audio

The Remarkable Dorothy L. Sayers

Click here to open a Print - Friendly PDF

A traveler enjoying a roadside stroll on the outskirts of London in the 1920s wouldn’t have been surprised to hear the pop-pop-pop of a Ner-A-Car motorcycle approaching on a bright afternoon.  Ner-A-Cars were a new and exciting development in the motoring world. Their owners enjoyed “the inspiration of flying on wheels” as they traversed their commute on this long, dark two-wheeled wonder.1 What might have surprised the observant traveler was that this Ner-A-Car was manned by a thirty-something woman “sitting bolt upright as if driving a chariot.”2 The observer might have been shocked to discover that the woman was six months pregnant. And who would have guessed that she was well on her way to becoming one of England’s most successful writers?

Ner-A-Cars were a new and exciting development in the motoring world. Their owners enjoyed “the inspiration of flying on wheels” as they traversed their commute on this long, dark two-wheeled wonder.1 What might have surprised the observant traveler was that this Ner-A-Car was manned by a thirty-something woman “sitting bolt upright as if driving a chariot.”2 The observer might have been shocked to discover that the woman was six months pregnant. And who would have guessed that she was well on her way to becoming one of England’s most successful writers?

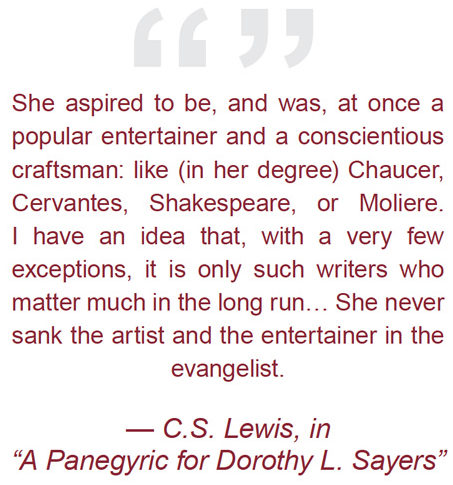

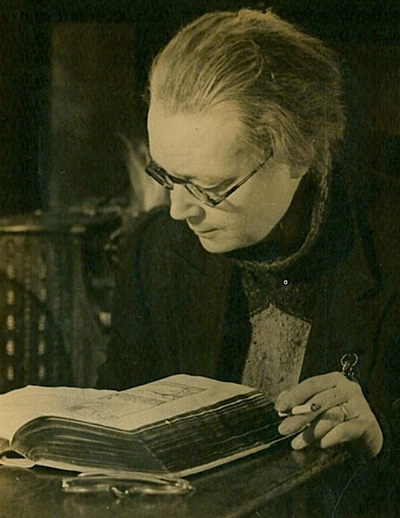

Dorothy L. Sayers (1893–1957), author of sixteen novels, ten plays, six translations, and twenty-four works of nonfiction, was an accomplished writer in multiple genres. Many admirers of C.S. Lewis have heard of her; she usually merits a handful of page references in the index of his biographies. Another class of reader — the fan of paperback mystery novels — knows Sayers as the creator of the memorable, near-perfect Lord Peter Wimsey. Yet again, dramatists might have performed her play The Zeal of Thy House. It is a testament to the breadth of her career that so many different readers know her name, if not all her works. From 1916, when her first book of poems was published, to her death in 1957, Sayers seemed to be everywhere on the English literary scene: she worked in advertising, was one of the first women to graduate from Oxford, became a celebrated novelist, developed a fascinating but orthodox approach to the Trinity, wrote stage plays, wrote radio plays, wrote articles on writing, translated the first two books of Dante’s Divine Comedy and was toward finishing the trilogy when she passed away, perhaps ironically, in the middle of Paradiso.

Sayers had a hard-hitting, humorous, competent style, and reading her would benefit many Christians today, particularly those inclined to use their faith as a cover for sloppy thinking. She had little patience for masking inability with piety, and her writing bears out her commitment to quality craftsmanship. My goal in this article is not only to introduce readers to the body of her work, but also to her colorful, confrontational personality. I have divided her writing under three headings: the Novelist, the Christian, and the Scholar. Naturally, each focus informs the other, and there never appears to have been a time when Sayers was not, at heart, all three. But one can’t properly take in forty years of writing without dividing such a banquet into digestible courses.

The Novelist

Dorothy Sayers identified herself as a writer from a young age. As an early twenty-something, she published two volumes of poetry.3 Yet it was prose that ultimately paid her bills. Her first novel, Whose Body?, was a murder mystery introducing Lord Peter Wimsey, an elegant gentleman-detective. Peter is brought in to solve the case of a dead body, lying in a bathtub and wearing nothing to help with identification but a pince-nez. He does so with suavity and humor. After some initial hurdles, Whose Body? came to the attention of an American publisher, who brought Sayers to the attention of the British market from the long way around. A second novel, Clouds of Witnesses, followed shortly thereafter.

Sayers would go on to write twelve novels, numerous short stories, and even a few faux histories about her whimsical hero. Wimsey, in turn, transported her from surviving month to month to a stable-enough income to support herself and others. Yet it was a gradual process, and much of her time writing the Wimsey novels was at night, while she worked a day job at London advertising agency. In fact, the poorer she felt, the richer Lord Peter became. She even joked about the contrast.

Sayers would go on to write twelve novels, numerous short stories, and even a few faux histories about her whimsical hero. Wimsey, in turn, transported her from surviving month to month to a stable-enough income to support herself and others. Yet it was a gradual process, and much of her time writing the Wimsey novels was at night, while she worked a day job at London advertising agency. In fact, the poorer she felt, the richer Lord Peter became. She even joked about the contrast.

When I was dissatisfied with my single unfurnished room I took a luxurious flat for him in Piccadilly. When my cheap rug got a hole in it, I ordered him an Aubusson carpet. When I had no money to pay my bus fare I presented him with a Daimler double-six, upholstered in a style of sober magnificence, and when I felt dull I let him drive it.4

Lord Peter’s wealth and abilities eventually set Sayers on the international scene. By the time she published her last Wimsey novel, Busman’s Honeymoon (1935), she was a best-selling author in England and America. Possibly one of her greatest novels — a mystery about bell ringing titled The Nine Tailors (1934) — was hailed by the New York Post as “one of the best mysteries available in the world today.”

5Sayers’s novel writing ended two years before the start of World War II. Although she never gave up storytelling, she did not return to the genre of detective fiction. She would write later that too much time with detective problems limits our field of vision, tricking us into thinking that the problem of, say, unemployment is just as predictably soluble and finite as figuring out whose body lies in the bathtub.6 She would direct her energies to a field of writing better equipped to deal with the complexities of war: Christian drama.

The Christian

Sayers seems to have fallen in love with the idea of writing drama before she became excited about writing specifically Christian drama. Busman’s Honeymoon was due to turn into a stage production when the dean of Canterbury Cathedral asked her to write a play to be performed in the church. Her predecessors for an invitation of this caliber were no less than T.S. Eliot and Charles Williams.7 She cautiously accepted the offer, and the result was a performance titled The Zeal of Thy House, in which Sayers uses a twelfth-century workaholic to explore the twin themes of quality craftsmanship and excessive pride. The play was popular, and Sayers found herself asked over and over about her Christianity. Her answers were pugnacious rather than personal, and she eventually put her thoughts into a Sunday Times article titled “The Greatest Drama Ever Staged Is the Official Creed of Christendom.” Dorothy L. Sayers, best-selling detective novelist and literary celebrity, had stated her faith in no uncertain terms. That the article caused a stir was, in Sayers’s opinion, not a compliment to the state of Christianity. What a tragedy that the Christian world was enraptured by “the spectacle of a middle-aged female detective-novelist admitting publicly that the judicial murder of God might compete in interest with the corpse in the coal hole.”

Sayers seems to have fallen in love with the idea of writing drama before she became excited about writing specifically Christian drama. Busman’s Honeymoon was due to turn into a stage production when the dean of Canterbury Cathedral asked her to write a play to be performed in the church. Her predecessors for an invitation of this caliber were no less than T.S. Eliot and Charles Williams.7 She cautiously accepted the offer, and the result was a performance titled The Zeal of Thy House, in which Sayers uses a twelfth-century workaholic to explore the twin themes of quality craftsmanship and excessive pride. The play was popular, and Sayers found herself asked over and over about her Christianity. Her answers were pugnacious rather than personal, and she eventually put her thoughts into a Sunday Times article titled “The Greatest Drama Ever Staged Is the Official Creed of Christendom.” Dorothy L. Sayers, best-selling detective novelist and literary celebrity, had stated her faith in no uncertain terms. That the article caused a stir was, in Sayers’s opinion, not a compliment to the state of Christianity. What a tragedy that the Christian world was enraptured by “the spectacle of a middle-aged female detective-novelist admitting publicly that the judicial murder of God might compete in interest with the corpse in the coal hole.”

8Nevertheless, Sayers had hit upon a thesis that was to drive both her fiction and nonfiction Christian works. Christianity was interesting and not only interesting; it was the best story ever told. This was not a new idea to Christendom, as anyone familiar with G.K. Chesterton knows, but Sayers gave it a twist. If the story of Christianity really was the most remarkable of tales, and if Jesus was a dangerous firebrand, then it was the responsibility of Christians to keep the romance alive. Yet the opposite had happened. Overuse of ecclesiastical language, stale curates, and excessive talk of Christ being meek and mild had made the Lion of Judah boring. She was blunt on this point. “Nobody cares…nowadays that Christ was ‘scourged, railed upon, buffeted, mocked and crucified’ because all those words have grown hypnotic with ecclesiastical use.” But if one wrote that Christ was “spiked upon the gallows like an owl on a barn-door,” this would not only get people’s attention, it would recall what actually happened to Him.

9Sayers had a chance to work out her thesis further with a BBC radio serial on the life of Christ. Her efforts to make Christ’s story more accessible, however, did not go unopposed. The Man Born to Be King involved a furious exchange of letters between Sayers and the BBC. Sayers had maintained that the apostles and Christ were to speak like regular persons and not “talk Bible … even at the risk of a little loss of formal dignity,” whereas the BBC was anxious to avoid unnecessary controversy.10 Sayers won most of the skirmishes, and the result was a lively radio drama in which Jesus speaks like a normal person, the apostle Matthew has a cockney accent, and the apostle Philip has no business sense. A snippet from the beginning of the fourth broadcast is a good indicator of Sayers’s style. Philip has just been cheated out of some money, and the apostles are unhappy with him.

Andrew: Six drachmas! Well, really, Philip!

Philip: I’m very sorry, everybody.

Simon: I daresay you are. But here’s me and Andrew and the Zebedees working all night with the nets to get a living for the lot of us — and then you go and let yourself be swindled by the first cheating salesman you meet in the bazaar —

Philip: I told you I’m sorry. Master, I’m very sorry. But it sounded all right when he worked it out.

Matthew: Fact is, Philip my boy, you’ve been had for a sucker.

11Partly because of the legacy of writers like Sayers, this passage may not seem controversial today. But at the time, it was explosive. Groups such as the Lord’s Day Observance Society and the Protestant Truth Society tried to get the radio drama banned. The protest went all the way to Parliament. But Sayers had an ally in the BBC’s director of Religious Broadcasting, who reminded her that all the protests were free publicity. Indeed they were: The Man Born to Be King was a remarkable success and a great encouragement to war-torn Britain.

12Sayers wrote Christian works outside of drama. Her Mind of the Maker, for example, is an innovative, orthodox comparison of the Trinity to human works of creation. Though she never claimed to be a theologian, The Mind of the Maker provides such ready accessibility to the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost that one of her biographers claimed that “she has managed, without any intellectual cheating, to bring God and man closer together.”13

The Scholar

Although as a young adult Sayers avowed that “I was never cut out for an academic career — I was really meant to be sociable,”14 she turned out to be a successful scholar. Her early language training in Latin, German, and French, her easy adoption of Italian, and her commitment to do a quality job as a writer made her a formidable translator and researcher. Her early affection for poetry, somewhat muted by the years of Wimsey novels and stage productions, returned in force toward the end of her life.

The Divine Comedy was to be the channel and the beneficiary of her zeal. It is odd that a woman so in love with poetry should have had so little exposure to perhaps the greatest poet of Europe, but until a 1944 air raid forced her underground with the first book that came to hand, Sayers and Dante had been poorly acquainted. According to her, it was love at first read:

The Divine Comedy was to be the channel and the beneficiary of her zeal. It is odd that a woman so in love with poetry should have had so little exposure to perhaps the greatest poet of Europe, but until a 1944 air raid forced her underground with the first book that came to hand, Sayers and Dante had been poorly acquainted. According to her, it was love at first read:

However foolish it may sound, the plain fact is that I bolted my meals, neglected my sleep, work, and correspondence, drove my friends crazy, and paid only a distracted attention to the doodle-bugs which happened to be infesting the neighborhood at the time, until I had panted my way through the Three Realms of the dead from the top to bottom and from bottom to top.15

Her first literary response to Dante was to write several letters to Charles Williams, who had provoked her interest in the poet in the first place. He was so taken by her energy and ability that he suggested publishing her letters. Unfortunately, his sudden death cut that plan short.16 But he had given Sayers a willing ear for her new enthusiasm. She also had another ear listening to her: the editor of Penguin Classics, who happened to be looking for a fresh translation of The Divine Comedy. He wanted something that would make Dante accessible to a broader audience; Sayers had a reputation for accessible writing and had, in fact, already thought through some of the limitations of current translations. “They are afraid to be funny,” she wrote to Williams. And “they insist on being noble and they end by being prim. But prim is the one thing Dante never is.”17 It was a good match. Sayers’s first volume, titled Hell, appeared in 1949. It is a testament to her abilities as a linguist that she learned Italian in order to translate Dante, first for her own enjoyment and then for Penguin. She published Purgatory in 1955, and both books were dedicated to the late Williams. She never finished Paradise because of her sudden death at home at the age of sixty-four.18

Conclusion

Sayers once requested that if any biography were written about her, it shouldn’t be until fifty years after her death.19 She deplored the idea of her youthful follies being broadcast for evaluation; what’s more, she did not think that the writer was necessarily more interesting than her works:

Sayers once requested that if any biography were written about her, it shouldn’t be until fifty years after her death.19 She deplored the idea of her youthful follies being broadcast for evaluation; what’s more, she did not think that the writer was necessarily more interesting than her works:

People are always imagining that if they get hold of the writer himself and, so to speak, shake him long enough and hard enough, something exciting and illuminating will drop out of him. But it doesn’t … If you notice, the first thing that usually crops up out of people’s biographies is the nonsense things about them, so that the general effect made is that the man wasn’t so very remarkable after all.20

For this reason and others, I have avoided focusing on Sayers’s personal relationships. They are surprising at times and certainly worth noting, but she would have wanted her works to come first as the best expression of herself. Every one of her writing stages — the novelist, the Christian, and the scholar — exhibit something of her humorous personality, boldness in controversy, and her willingness to put her intellect at the service of God the Father, God the Son, and God the Spirit. She never claimed to be a mystic and envied Williams his lively spiritual nature,21 but she knew irrationality and lazy thinking when she saw it; I suspect that she would have been as intimidating an interviewer as ever Lewis was in his Oxford rooms.

I’d like to end this article with a brief note on education. Long-standing critiques of American education have led to a rise of Christian schools that are near-rabid about producing classically trained, competent, faithful students. I teach at such a school, and I’m grateful for its position on high-quality academics. Every month we hold information meetings for parents willing to partner with us in this task. And what do we give them as food for thought? An essay by an Oxford graduate, novelist, playwright, apologist, scholar, and motorcyclist. We give them the “Lost Tools of Learning” by Dorothy L. Sayers.

|

Notes: |

Lindsey Scholl

TeacherLindsey Scholl, Teacher, holds a doctorate in Roman History from the University of California, Santa Barbara and a Master’s degree in Medieval History from the University of Missouri at Columbia. She has taught at Trinity Classical School in Houston, Texas, for nearly a decade, mostly Latin and Humanities in some form. She is currently teaching Medieval History and Literature, Creative Writing, in addition to serving as the Latin Chair. Dr. Scholl has presented various academic papers but also enjoys speaking about Church History and Christian Life at venues ranging from girls’ camps to education conferences.

Recommended Reading:

Barbara Reynolds, Dorothy L. Sayers: Her Life and Soul (St. Martin’s Press, 1997)

Mystery writer Dorothy Sayers is loved and remembered, most notably, for the creation of sleuths Lord Peter Wimsey and Harriet Vane. As this biography attests, Sayers was also one of the first women to be awarded a degree from Oxford, a playwright, and an essayist — but also a woman with personal joys and tragedies. Here, Reynolds, a close friend of Sayers, presents a convincing and balanced portrait of one of the 20th century’s most brilliant, creative women.

COPYRIGHT: This publication is published by C.S. Lewis Institute; 8001 Braddock Road, Suite 301; Springfield, VA 22151. Portions of the publication may be reproduced for noncommercial, local church or ministry use without prior permission. Electronic copies of the PDF files may be duplicated and transmitted via e-mail for personal and church use. Articles may not be modified without prior written permission of the Institute. For questions, contact the Institute: 703.914.5602 or email us.

COPYRIGHT: This publication is published by C.S. Lewis Institute; 8001 Braddock Road, Suite 301; Springfield, VA 22151. Portions of the publication may be reproduced for noncommercial, local church or ministry use without prior permission. Electronic copies of the PDF files may be duplicated and transmitted via e-mail for personal and church use. Articles may not be modified without prior written permission of the Institute. For questions, contact the Institute: 703.914.5602 or email us.

-

Recent Podcasts

Questions That Matter – Heather and Ashley Holleman and the Greatness of Conversation

by Randy Newman, Heather Holleman on February 14, 2025We live in a conversation-starved time when loneliness...Read More

-

Doubting after Faith – Dr. Bobby Conway’s Story

by Bobby Conway, Jana Harmon on February 14, 2025

-

Emotions, Divine Suffering, and Biblical Interpretation

by Kevin J. Vanhoozer on February 7, 2025

-

Recent Publications

The Impact of Technology on the Christian Life

by Tony Reinke on February 14, 2025"It’s applied technique. So it’s an art. It’s...Read More

-

C.S. Lewis and the Crisis of the Modern Self

by Thaigo M. Silva on February 1, 2025

-

Why Are Christians So Hypocritical?

by William L. Kynes on January 1, 2025

0

All Booked

0.00

All Booked

0.00

All Booked

23993

Heart and Mind Discipleship Live Online Small Group 8:00 PM ET

https://www.cslewisinstitute.org/?event=heart-and-mind-discipleship-live-online-small-group-800-pm-et&event_date=2025-02-25®=1

https://www.paypal.com/cgi-bin/webscr

2025-02-25

Next coming event

Days

Hours

Minutes

Seconds

Heart and Mind Discipleship Live Online Small Group 8:00 PM ET

On February 25, 2025 at 8:00 pmSpeakers

Lindsey Scholl

Teacher

Team Members

Lindsey Scholl

TeacherLindsey Scholl, Teacher, holds a doctorate in Roman History from the University of California, Santa Barbara and a Master’s degree in Medieval History from the University of Missouri at Columbia. She has taught at Trinity Classical School in Houston, Texas, for nearly a decade, mostly Latin and Humanities in some form. She is currently teaching Medieval History and Literature, Creative Writing, in addition to serving as the Latin Chair. Dr. Scholl has presented various academic papers but also enjoys speaking about Church History and Christian Life at venues ranging from girls’ camps to education conferences.