Back to series

Recommended Reading:

Download or Listen to Audio

The Heroics of Weakness

Click here to open a Print - Friendly PDF

On a trip to the family cottage, my mother, brother, and I had a discussion about earliest memories. I recalled an experience in an oxygen tent with a teddy bear and my grandmother; I was only a year and a half old. I’d had difficulty breathing, due to a very premature birth, and stayed in a Florida hospital as my lungs struggled to do something that’s so natural it’s normally automatic. It’s a powerful memory, I think, because it’s drenched in weakness.

This weakness became deeply ingrained during my college experience as I grappled with arthritic joint pain and muscle fatigue, unexpected effects of an active life lived with cerebral palsy (CP). In short, cerebral palsy stems from damage to the brain, related to premature birth complications, that results in reduced mobility, muscle function, and motor skills.

This weakness became deeply ingrained during my college experience as I grappled with arthritic joint pain and muscle fatigue, unexpected effects of an active life lived with cerebral palsy (CP). In short, cerebral palsy stems from damage to the brain, related to premature birth complications, that results in reduced mobility, muscle function, and motor skills.

During college I often felt exhausted and somewhat frustrated, facing this new, unexpected physical challenge. I would pray and plead for permanent relief from the pain, often in the dead of night, but God would provide an unexpected prescription, showing that perseverance is the unexpected — and greater — miracle. As the apostle Paul writes: “But He said to me, ‘My grace is sufficient for you, for My power is made perfect in your weakness’” (2 Cor. 12:9).

Weakness isn’t something our culture celebrates. Society encourages emulation of people who possess power: politicians, athletes, authors, musicians, Wall Street wiz-kids, and movie and television stars. Most of us recognize we aren’t them, that they have a level of temporal success we do not – but wish we did; many of us secretly wish we were them, as these are our culture’s “heroes.” Conversely, our culture ignores the weak, saying, at best, they should be helped because they cannot live, achieve, or contribute on their own.

When I worked on Capitol Hill for a member of Congress, a colleague expressed that “I didn’t make sense.” In short, because I have a disability, worked for a representative, and expressed a familiarity with and fondness for fandoms in pop-culture frequently referenced on The Big Bang Theory (such as Star Wars, Lord of the Rings, or superheroes from Marvel and DC Comics), there wasn’t a mental box to put me in. I defied explanation. In that moment, I had to explain that I wasn’t interested in fitting into a certain mold or wasting time and energy conforming to what others thought I should be. Conversely, that incident forced me to articulate who I knew myself to be (or not to be).

Growing up, I gravitated toward unexpected heroes. My first hero was Luke Skywalker, a farm boy living on a backwater desert planet. I developed a lifelong love for Star Wars that led me to Yoda, or, as I call him, the “Foolish Muppet.” In The Empire Strikes Back, Luke Skywalker travels to another planet, Dagobah, to learn from Yoda, the great Jedi Master who instructed Luke’s late teacher, Obi-Wan Kenobi. On Dagobah, Luke comes across a small goblin-like creature who hobbles around with a cane and has syntax issues; Luke thinks him foolish. The creature claims to know Yoda and where he lives, so Luke follows. Soon Luke experiences a revelation — aided by Obi-Wan — that becomes stunned fascination: this aged creature, shrouded in weakness, is Yoda.

In the original Star Wars trilogy, most of Luke Skywalker’s moments of revelation happen because of Obi-Wan, who, though physically deceased, still able to advise Luke. Learning about his father and destroying the Death Star in A New Hope, revealing the goblin’s identity as Yoda in The Empire Strikes Back, learning he has a sister in Return of the Jedi – all of these moments are facilitated by Obi-Wan, and they aid in Luke’s transformation from farm boy to Jedi Knight, from nobody to galactic hero.

Transformation doesn’t happen without revelation, and revelation can’t happen without foolishness.

In Star Wars, Obi-Wan functions as a counselor for Luke. I’d argue that, in our lives, the Holy Spirit works in a similar manner. In fact, counselor is what Jesus calls the Holy Spirit in the Gospel of John. It’s the Spirit, often in tandem with God’s Word, who aids in revelation – leading to transformation. To embrace this means that you’ve got to embrace who Jesus says He is and His finished work on the cross. (Paul even wrote that this is foolishness to those who don’t believe it.)

Sometimes we’re asked to embrace a particular kind of foolishness, the foolishness of place, modeled by Yoda’s years of self-imposed exile on a backwater swamp planet. Last summer I traveled not to a swamp but a desert, like Luke’s home planet of Tatooine, when I spent time at the Lillian Trasher Orphanage in southern Egypt. Like Luke Skywalker on Dagobah, I wondered why I was there, parsecs outside my comfort zone. In the midst of my wondering, I encountered a two-year-old boy named Yessa, and my weakness allowed him to take a first step into a larger world.

Sometimes we’re asked to embrace a particular kind of foolishness, the foolishness of place, modeled by Yoda’s years of self-imposed exile on a backwater swamp planet. Last summer I traveled not to a swamp but a desert, like Luke’s home planet of Tatooine, when I spent time at the Lillian Trasher Orphanage in southern Egypt. Like Luke Skywalker on Dagobah, I wondered why I was there, parsecs outside my comfort zone. In the midst of my wondering, I encountered a two-year-old boy named Yessa, and my weakness allowed him to take a first step into a larger world.

Yessa is both nonverbal and calcium deficient, which contributed to his inability to walk. As I watched him with my teammates, mental lightning struck, a potentially life-changing what-if: what if we put Yessa in my walker? I adjusted it and motioned for him to be brought over. With that aid, he took his first independent steps. In that moment, I realized I’d been sent halfway across the world — to a place where I felt useless — to facilitate the first footsteps of an orphaned toddler. A few days later, as I went to say good-bye, he came out wearing a Yoda shirt – despite the language barrier and no way of the staff knowing I loved the character. Did they see me — or Yessa — as characters in a grand story?

My love for “foolish” heroes also includes a strong affinity for comic book hero Charles Xavier. He’s a wheelchair-bound professor who teaches his students — the community known as the X-Men — how to use their abilities for good and heroic ends. He leads his students as Professor X and is perceived as weak and incapable, but this weakness shrouds both incredible telepathic power and a deep understanding of the human condition and the need for hope as shown in the summer blockbuster X-Men: Days of Future Past.

In the film, Xavier’s mobility and mutant ability are tied together. He takes a drug that suppresses his powers but allows mobility. It’s not until the younger Xavier encounters the older professor, via time travel of the mind, and the older entreats the younger to hope again, speaking to a deep ability to bear the pain of others, that the younger Charles is willing to relinquish his drug-induced mobility (thus sacrificing something most take for granted) to embrace a unique capacity to engage with a suffering world.

In the film, Xavier’s mobility and mutant ability are tied together. He takes a drug that suppresses his powers but allows mobility. It’s not until the younger Xavier encounters the older professor, via time travel of the mind, and the older entreats the younger to hope again, speaking to a deep ability to bear the pain of others, that the younger Charles is willing to relinquish his drug-induced mobility (thus sacrificing something most take for granted) to embrace a unique capacity to engage with a suffering world.

With Charles there’s a sequence of character development that affirms what the apostle Paul wrote in Romans 5: suffering develops perseverance; perseverance develops character; character develops into hope (a confident expectation of the future that is rooted in Christ’s finished work on the cross). It’s worth noting that character and hope come to older Charles after the suffering and perseverance of his younger self. In our lives, we want the character and hope — that confident expectation — without the suffering and persevering; we want the epic stories but without the scars as evidence that they happened. But this on-screen presence supports Paul’s particular progression.

Xavier speaks to power in weakness in a way that deeply resonates with me, because his telepathic abilities are linked to his mobility. As his mental powers function, his legs do not. Conversely, if Xavier were to possess full mobility, his telepathy and professorially imparted understanding of the world — influenced by his disability — would diminish.

Long before George Lucas imagined Yoda or Stan Lee created Professor X, the apostle Paul wrote about weakness and foolishness, the ideas that both these characters embody, in his letter to the church at Corinth: “but God chose what is foolish in the world to shame the wise; God chose what is weak in the world to shame the strong; God chose what is low and despised in the world, even things that are not, to bring to nothing things that are, so that no human being might boast in the presence of God.” (1 Cor. 1:27-29, ESV). Throughout life I have strongly identified with these characters as examples in popular culture of a biblical truth I too have embraced.

Long before George Lucas imagined Yoda or Stan Lee created Professor X, the apostle Paul wrote about weakness and foolishness, the ideas that both these characters embody, in his letter to the church at Corinth: “but God chose what is foolish in the world to shame the wise; God chose what is weak in the world to shame the strong; God chose what is low and despised in the world, even things that are not, to bring to nothing things that are, so that no human being might boast in the presence of God.” (1 Cor. 1:27-29, ESV). Throughout life I have strongly identified with these characters as examples in popular culture of a biblical truth I too have embraced.

In Scripture God takes real people of whom the world thinks little, weak in some way or another, and displays His fantastic and incredible power through them. Moses was a murderer with a speech problem, yet he led a nation to freedom and promise. David was a teenaged shepherd who brandished a sling and felled a giant, the symbol of a tyrannical empire (events echoed in Luke Skywalker’s role in the destruction of the Death Star in Star Wars, Episode IV: A New Hope). God loves to do the unexpected and through it displays Himself to His creation.

The pages of His Story are full of the unexpected, climaxing in the fulfillment of an age-old prophecy: God would become a man and defeat the ancient enemy of the souls of humankind at the Hill of Skulls, not through power or force, but by weakness, sacrifice, and dying. Only then would He show power in defeating not only the Enemy of Souls, but also Death through resurrection.

Not long ago, on a street corner in Israel, a group of college students prayed physical healing over me, expecting immediate, and miraculous, results. When those results did not manifest, the students asked if I at least felt a degree of peace about my circumstances. I told them that the peace they wanted me to have through a physical healing I already had in the midst of my weakness because of God-given perseverance.

Not long ago, on a street corner in Israel, a group of college students prayed physical healing over me, expecting immediate, and miraculous, results. When those results did not manifest, the students asked if I at least felt a degree of peace about my circumstances. I told them that the peace they wanted me to have through a physical healing I already had in the midst of my weakness because of God-given perseverance.

Those students came seeking a miracle, and I maintain they were given one, but they missed it. Instead of witnessing a miracle of healing, they were given one of endurance, something they did not expect. It’s a question of what is greater; what has greater impact and a longer life: an instantaneous change of physical state or a daily, consistent, faithful, enduring in the midst of discomfort and challenge?

Truthfully, we’re all weak in ways visible and invisible. Nevertheless, weakness can unexpectedly draw others toward a deeper understanding of who God is — and who we are as His creation — if we embrace it.

A farm boy, a Jedi, a professor, a shepherd, and the Savior embraced weakness and accomplished heroic things. What might we accomplish, for a purpose beyond ourselves, with a willingness to embrace our own heroic weaknesses?

|

Notes: |

Aaron Welty

Motivational SpeakerAaron Welty was diagnosed with Cerebral Palsy as a new born, he overcame those early years of low expectations to serve as the Senior Legislative Assistant for Michigan’s 11th Congressional District, wherein he focused on a variety of policy issues. He graduated from Cedarville University in 2006 with a degree in Public Administration. Prior to working on Capitol Hill, Aaron worked in Marketing and Media at The Heritage Foundation. Passionate about the ideas of individual purpose and destiny, his unique story of faith, family, perseverance and chasing dreams has been shared on NBC Nightly News, various radio programs, Roll Call – a nationally syndicated newspaper – and Facing Life Head On, a life-issues focused television program.

Recommended Reading:

Joni Eareckson Tada and Stephen Estes – When God Weeps: Why Our Sufferings Matter to the Almighty (Zondervan, 1997)

If God is loving, why is there suffering? What’s the difference between permitting something and ordaining it? When bad things happen, who’s behind them — God or the devil? When suffering touches our lives, questions like these suddenly demand an answer. From our perspective, suffering doesn’t make sense, especially when we believe in a loving and just God. After more than thirty years in a wheelchair, Joni Eareckson Tada’s intimate experience with suffering gives her a special understanding of God’s intentions for us in our pain. In When God Weeps, she and lifelong friend Steven Estes probe beyond glib answers that fail us in our time of deepest need. Instead, with firmness and compassion, they reveal a God big enough to understand our suffering, wise enough to allow it — and powerful enough to use it for a greater good than we can ever imagine.

COPYRIGHT: This publication is published by C.S. Lewis Institute; 8001 Braddock Road, Suite 301; Springfield, VA 22151. Portions of the publication may be reproduced for noncommercial, local church or ministry use without prior permission. Electronic copies of the PDF files may be duplicated and transmitted via e-mail for personal and church use. Articles may not be modified without prior written permission of the Institute. For questions, contact the Institute: 703.914.5602 or email us.

COPYRIGHT: This publication is published by C.S. Lewis Institute; 8001 Braddock Road, Suite 301; Springfield, VA 22151. Portions of the publication may be reproduced for noncommercial, local church or ministry use without prior permission. Electronic copies of the PDF files may be duplicated and transmitted via e-mail for personal and church use. Articles may not be modified without prior written permission of the Institute. For questions, contact the Institute: 703.914.5602 or email us.

-

Recent Podcasts

From Anti-Christian to Pastor – Brian Smith’s Story

by Jana Harmon, Brian Smith on January 17, 2025Brian grew up in a small Georgia town...Read More

-

Time With God

by Aimee Riegert, J.I. Packer on January 10, 2025

-

Faith and Reason – Henare Whaanga’s Story

by Henare Whaanga, Jana Harmon on January 3, 2025

-

Recent Publications

Why Are Christians So Hypocritical?

by William L. Kynes on January 1, 2025Oh, the hypocrisy of those Christians—they talk so...Read More

-

How Artists and Their Art Can Point Us to the Creator

by Russ Ramsey on December 2, 2024

-

What about Jesus’s Childhood?

by Jim Phillips on December 1, 2024

0

All Booked

0.00

All Booked

0.00

All Booked

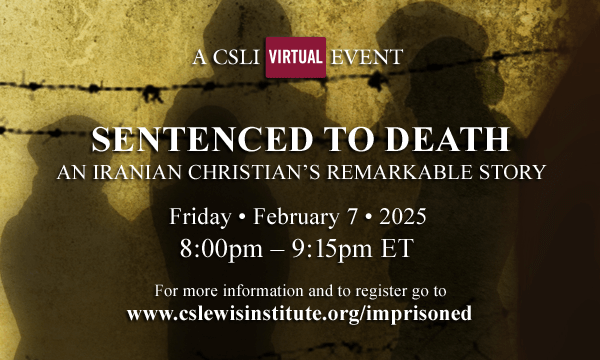

23931

GLOBAL EVENT: Sentenced to Death with Maryam Rostampour-Keller, 8:00PM ET

https://www.cslewisinstitute.org/?event=global-event-sentenced-to-death-with-maryam-rostampour-keller-800pm-et&event_date=2025-02-07®=1

https://www.paypal.com/cgi-bin/webscr

2025-02-07

Next coming event

Days

Hours

Minutes

Seconds

GLOBAL EVENT: Sentenced to Death with Maryam Rostampour-Keller, 8:00PM ET

On February 7, 2025 at 8:00 pmSpeakers

Aaron Welty

Motivational Speaker

Team Members

Aaron Welty

Motivational SpeakerAaron Welty was diagnosed with Cerebral Palsy as a new born, he overcame those early years of low expectations to serve as the Senior Legislative Assistant for Michigan’s 11th Congressional District, wherein he focused on a variety of policy issues. He graduated from Cedarville University in 2006 with a degree in Public Administration. Prior to working on Capitol Hill, Aaron worked in Marketing and Media at The Heritage Foundation. Passionate about the ideas of individual purpose and destiny, his unique story of faith, family, perseverance and chasing dreams has been shared on NBC Nightly News, various radio programs, Roll Call – a nationally syndicated newspaper – and Facing Life Head On, a life-issues focused television program.