Back to series

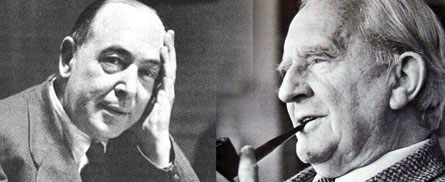

C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien

Click here to open a Print - Friendly PDF

C.S. Lewis was able to make close friendships. And those friendships influenced and shaped his own journey at most of the important turning points of his life—except for one: his love for and marriage to Joy Davidman. His older brother, Warren, was the only friend who knew about that. Lewis made that decision and the steps that led to it by himself. Joy Davidman was a beautiful gift from the Lord that both of them deeply appreciated.

Most of Lewis’s friends were baffled by Lewis’s marriage to Joy Davidman. But it especially baffled J.R.R. Tolkien, one of his closest friends, and caused a strain in Lewis’s and Tolkien’s relationship. Nevertheless, the richness and depth of their friendship outlasted that strain.

Tolkien and Lewis shared much in common. Both had lost their mothers to death at an early age, and Tolkien had lost his father as well. Both as young boys made close friends with fellow students at school who shared their love for stories. Both were young soldiers who fought in the First World War on the French front. Both were seriously wounded, both saw death in battle, and both lost close friends in that brutal war of the trenches.

As a lad, John Ronald Reuel Tolkien and his brother suffered the untimely death of their mother, Mabel. They were both adopted by Father Francis Xavier Morgan, a priest who had been an assistant to Cardinal John Henry Newman. Father Morgan loved these young boys, and guided and provided for the education of the brothers until their adult years. The influence in Tolkien’s life of Father Morgan cannot be overemphasized. Tolkien said, “I witnessed half comprehending the heroic sufferings and early death in extreme poverty of my mother who brought me into the Church; and I received the astonishing charity of Francis Morgan.

But I fell in love with the Blessed Sacrament from the beginning.” Tolkien would faithfully attend the mass everyday of his life, and he would name his first son, who would himself become a Roman Catholic priest, John Francis Reuel Tolkien. A kind and strong priest, Francis Morgan left a profound imprint upon J.R.R. Tolkien.

For the young C.S. Lewis, the most formative influence upon his life and mind was that of his mentor and tutor, W.T. Kirkpatrick, who taught Lewis as a private, live-in student when Lewis was 16 and 17 years old. Lewis would later write this of Kirkpatrick, in a letter to his father in 1921: “I owe to him in the intellectual sphere as much as one human being can owe another…it was an atmosphere of unrelenting clearness and rigid honesty of thought that one breathed from living with him, and this I shall be the better for as long as I live.”

Tolkien’s career path developed out of his love of language. He began as a lexographer, went on to Leeds University, and then to Oxford University, where he eventually became the Merton Professor of English Language and Literature. One friend of both Lewis and Tolkien, Owen Barfield, described Lewis as “in love with the imagination” and Tolkien as “in love with language.” Tolkien’s Middle Earth project began as he told hobbit stories to his son John at bed time. He called this project my “stuff,” and he credits a friend who offered him the gift of “sheer encouragement.” Eventually, Tolkien agreed to the publication of his stories: first The Hobbit, and then his masterpiece, The Lord of the Rings trilogy. The encouraging friend was another Oxford scholar, C.S. Lewis.

J.R.R. Tolkien’s fundamental and daily walk of faith in Jesus Christ was discovered first from his beloved Father Morgan and participation in the worship of the Catholic Mass, with its focus on the death of Christ and his victory over death, sin, and the power of evil on our behalf. Tolkien grew to have a certitude and confidence in the powerful grace of God that in the end overcomes the terrors of evil. Evil may itself be strong, but Tolkien built his confidence upon St. Paul’s radical affirmation in Romans 5 that “where sin increased, the grace of God increased more.” Evil has cumulative force and inner power of its own, but the goodness of ultimate reality rendered in Jesus Christ has even greater power.

The adventures in Tolkien’s stories live within this certitude of their author.

For Lewis, the journey toward faith in Christ started in the territory of a youthful atheism, following a roadway more like an alpine trail that moves to the right and then to the left, sometimes veering farther away from the destination, and yet finally arriving in an open place of trust in the one who is Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. It started with the honesty and clearness of W.T. Kirkpatrick who, though himself an atheist, taught Lewis to think for himself and to search for answers wherever they are.

In France, while at war, Lewis met a brave and good comrade in arms who was killed in battle before his eyes. Lewis tells about this man in his book Surprised by Joy. The goodness in this man surprised Lewis and unnerved his cynicism. He wrote, “In my own battalion also I was assailed. Here I met one Johnson (on whom be peace) who would have become a life-long friend if he had not been killed…in him I found dialectical sharpness such as I had hitherto known only in Kirkpatrick, but coupled with youth and whim and poetry. He was moving toward theism…But it was not this that mattered. The important thing was that he was a man of conscience.” This man, who was the commander of Lewis’s company, had been a marker of goodness and integrity and in his own way a witness to the reality of God.

Also in France, Lewis was treated for trench mouth and while in a hospital tent, he read a volume of G.K. Chesterton essays. Lewis wrote of Chesteron, “I liked him for his goodness. I can attribute this taste to myself freely (even at that age) because it was a liking for goodness which had nothing to do with any attempt to be good myself…In reading Chesterton, as in reading [George] MacDonald, I did not know what I was letting myself in for. A young man who wishes to remain a sound atheist cannot be too careful of his reading. There are traps everywhere…”

Also in France, Lewis was treated for trench mouth and while in a hospital tent, he read a volume of G.K. Chesterton essays. Lewis wrote of Chesteron, “I liked him for his goodness. I can attribute this taste to myself freely (even at that age) because it was a liking for goodness which had nothing to do with any attempt to be good myself…In reading Chesterton, as in reading [George] MacDonald, I did not know what I was letting myself in for. A young man who wishes to remain a sound atheist cannot be too careful of his reading. There are traps everywhere…”

Both Tolkien and Lewis loved stories of the marvelous, and that affection for stories drew them together in 1926 at a reading group Tolkien had founded called the “Coalbiters.” They gradually came together with a few other friends to meet on a regular basis, to drink beer together and talk about books. These friends included Hugo Dyson, who was also an Oxford scholar; Dr. Havard, a medical doctor; C.S. Lewis’s brother, Warren; Charles Williams, who worked for Oxford University Press; and others who came occasionally.

They called themselves the Inklings. These men were Christians. It was a particular, long talk between Dyson, Tolkien, and Lewis that became the decisive moment of discovery for C.S. Lewis. Tolkien helped him to understand the most radical truth about Jesus Christ as the world’s unique, totally-by-surprise, breakthrough of the divine who resolves the world’s catastrophe of human sin, death, and the power of evil.

The pieces of a grand puzzle came together, and Lewis decided to believe in the deity of Jesus Christ. He explained it to his friend Arthur Greeves: “It was the long talk with Tolkien and Dyson that had much to do with it.”

C.S. Lewis dedicated his book, The Screwtape Letters, to his friend J.R.R. Tolkien, and Tolkien dedicated his Lord of the Rings to the Inklings. It was also Tolkien who was the key influence in persuading C.S. Lewis to accept the professorship offered by Cambridge in 1954.

Lewis honored his experience of friendship with Tolkien and his other friends in the Inkling group in the book, The Four Loves (1960). In that important study of love, he wrote that whereas lovers stand face to face, friends stand side by side. The friendship among the Inklings was about the truths they held in common. In friendships like this, Lewis says there is the “what you too! I thought I was the only one” factor, the recognition of a shared vision (p. 96, The Four Loves). These words of Lewis help us to appreciate the healthy friendships that marked Lewis’s life. Tolkien’s friendships were not as extensive as were Lewis’s, but they both were marked with the “what you too! I thought I was the only one” factor.

These two story tellers gave to each of us a grand gift of the joy of adventure in their stories of the marvelous. They made us want to read, and for many of us to want to write stories of our own.

For the unsuspecting agnostic or atheist, both of these writers will catch us offguard. There is a sheer goodness and kindness at the core of the resolving surprise that happens to two young hobbits, Frodo and Sam, at Mt. Doom in Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings. It is a tender goodness that overcomes the dreadful power of the ring.

That very goodness in the Return of the King is an unforgettable moment that prepares us for the great breakthrough of the powerful grace of God. Gandalf, in the castle of King Theoden, challenges every fear we have that makes us want to stay safely hidden from the clear cold air of life. Tolkien helps us understand the cruelty of evil and its own inner weakness and rage that finally becomes destructive to evil itself.

Lewis helps us discover the breakthrough of God’s love and truth in the “enormous exception” that G.K. Chesterton predicted. We meet the golden lion Aslan, Son of the Emperor from beyond the sea. Lewis once wrote to a friend about the seven Narnia stories, “I wondered what the redeemer would be like given a place like Narnia.” Now we have seen it for ourselves, and our lives are not the same. Both men are like friends we wish we knew, both oddly contemporary to us as their stories, letters, essays, and persuasive books allow us to know how they think, and we are the better for it.

C.S. Lewis died in his beloved home, the Kilns, on November 23, 1963. J.R.R. Tolkien was at the graveside of his friend with a few of their Oxford friends and one family member, Lewis’s stepson Douglas. Lewis was buried in the churchyard of the Headington Trinity Parish; on his grave are the words that were imprinted on the calendar of his house in Belfast on the day his mother died: “Men must endure their going hence.”

Earlier that year, Lewis had written to Tolkien, “All my philosophy of history hangs upon a sentence of your own, ‘Deeds were done which were not wholly in vain.’” Lewis is quoting from The Fellowship of the Ring.

J.R.R. Tolkien died on September 2, 1973. His grave is in the Catholic Cemetery at Oxford, a few feet from his oldest son, the Rev. Father John Reuel Francis Tolkien, who died in 2003.

Both men are in their books, and their books are in our hearts.

Earl Palmer

Pastor Earl Palmer (1931 - 2023) an American Presbyterian minister, served in pastoral ministries at University Presbyterian Church in Seattle, Union Church in Manila, First Presbyterian Church of Berkeley, and The National Presbyterian Church in Washington, D.C. Palmer is known for his expositional preaching and teaching style. Palmer has written over 20 books which include, To Run the Race: Paul's Second Letter to Timothy, Trusting God: Christian Faith in a World of Uncertainty and Called to be a People of the Gospel: St. Paul’s New Testament Letter to the Ephesians. Palmer also served on the boards of Princeton Theological Seminary, New College Berkeley, Whitworth University and Regent College. COPYRIGHT: This publication is published by C.S. Lewis Institute; 8001 Braddock Road, Suite 301; Springfield, VA 22151. Portions of the publication may be reproduced for noncommercial, local church or ministry use without prior permission. Electronic copies of the PDF files may be duplicated and transmitted via e-mail for personal and church use. Articles may not be modified without prior written permission of the Institute. For questions, contact the Institute: 703.914.5602 or email us.

COPYRIGHT: This publication is published by C.S. Lewis Institute; 8001 Braddock Road, Suite 301; Springfield, VA 22151. Portions of the publication may be reproduced for noncommercial, local church or ministry use without prior permission. Electronic copies of the PDF files may be duplicated and transmitted via e-mail for personal and church use. Articles may not be modified without prior written permission of the Institute. For questions, contact the Institute: 703.914.5602 or email us.

-

Recent Podcasts

From Anti-Christian to Pastor – Brian Smith’s Story

by Jana Harmon, Brian Smith on January 17, 2025Brian grew up in a small Georgia town...Read More

-

Time With God

by Aimee Riegert, J.I. Packer on January 10, 2025

-

Faith and Reason – Henare Whaanga’s Story

by Henare Whaanga, Jana Harmon on January 3, 2025

-

Recent Publications

Why Are Christians So Hypocritical?

by Christopher L. Reese on January 1, 2025Oh, the hypocrisy of those Christians—they talk so...Read More

-

How Artists and Their Art Can Point Us to the Creator

by Russ Ramsey on December 2, 2024

-

What about Jesus’s Childhood?

by Jim Phillips on December 1, 2024

0

All Booked

0.00

All Booked

0.00

All Booked

23931

GLOBAL EVENT: Sentenced to Death with Maryam Rostampour-Keller, 8:00PM ET

https://www.cslewisinstitute.org/?event=global-event-sentenced-to-death-with-maryam-rostampour-keller-800pm-et&event_date=2025-02-07®=1

https://www.paypal.com/cgi-bin/webscr

2025-02-07

Next coming event

Days

Hours

Minutes

Seconds

GLOBAL EVENT: Sentenced to Death with Maryam Rostampour-Keller, 8:00PM ET

On February 7, 2025 at 8:00 pmCategories

Speakers

Earl Palmer

Pastor

Team Members